Why Old Places Matter: A Oneness of Conservation and Preservation, and the Spirit of Old Town

As someone who has spent a lifetime in medicine and public service, I’ve always believed that healing is about more than a diagnosis or prescription. True healing begins with what’s around us, our environment—the air we breathe, the water we drink, the food we eat, the land we walk. That belief has only deepened in recent years as my wife, Tracy, and I have devoted ourselves to the conservation and preservation of a small but meaningful place we call home: Old Town.

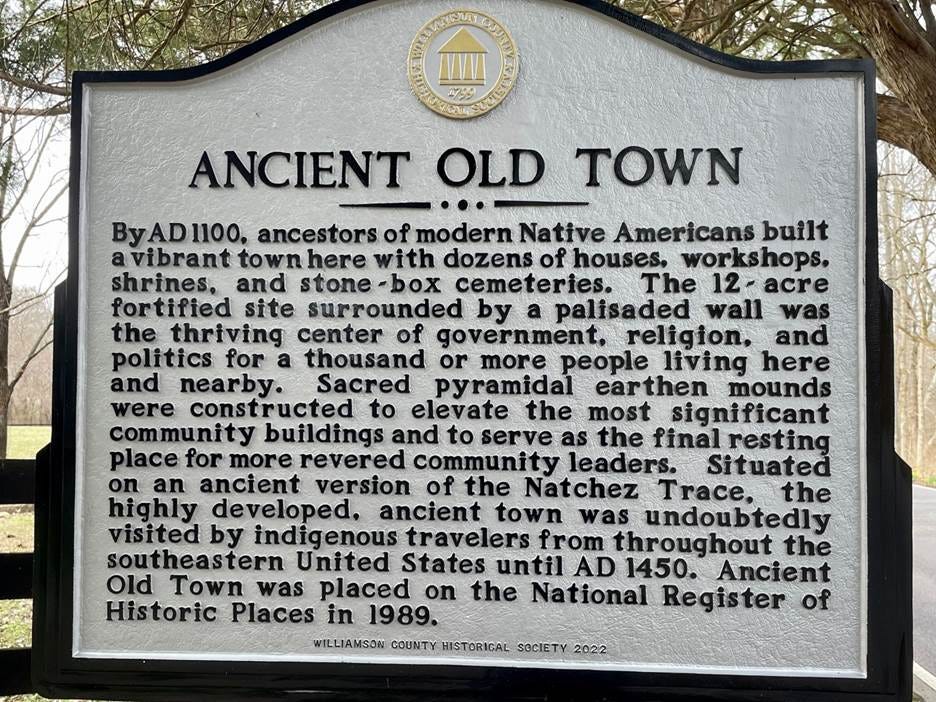

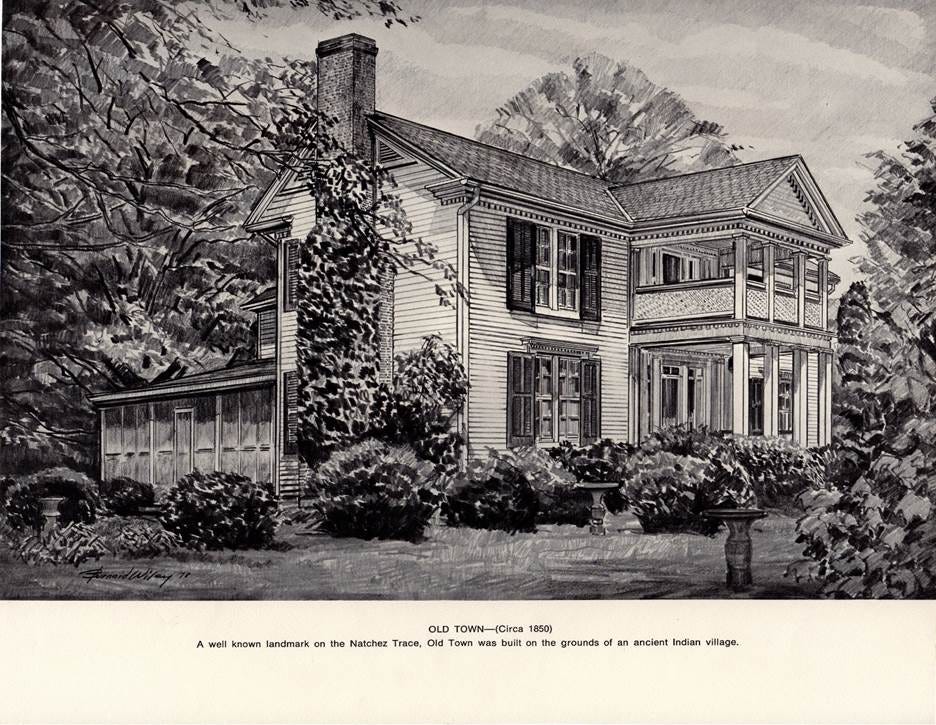

Old Town is a 64-acre farm nestled along the Harpeth River in Williamson County, Tennessee. It got its name from Choctaw and Chickasaw peoples who, when hunting the region in the 1500s, found vestiges of an older village that had been deserted 150 years prior. Today, it’s where Tracy and I live—our home, and the place of animals and livestock, chickens and geese, dogs and cats, horses and donkeys, sheep and goats. It is full of fauna and flora, plants and trees. Yes, it’s our residence, but it is more truly a place we steward.

Its roots stretch deep—to the Mississippian-era (850–1350 AD) civilization who first cultivated this land, to the 1846 farmhouse that still stands at its center, and to the generations of families who have found meaning, sustenance, and connection here. What we do at Old Town is less about ownership and more about reverence. We are caretakers of its story, and our task is to keep that narrative vibrant and accessible for others.

The renowned landscape architect Thomas Woltz—and close friend—joined Tracy and me at Old Town last week, along with Gavin Duke and new and old friends from the Southeastern Chapter of the Institute of Classical Architecture & Art. Just days earlier, Tracy and I had been with Thomas in New York City where he was honored with the Frederic Church Award by the Olana Partnership for his visionary work upholding harmony between art, culture, and nature. Fittingly, Liz McLaurin, who leads The Land Trust for Tennessee, joined us both in New York and Tennessee for both occasions.

Tracy and I listened carefully to Thomas’s formal remarks in the Rainbow Room in New York that evening, and we have reflected on them together ever since, but most notably during our walk with Thomas around Old Town in Middle Tennessee two days later.

As we think conservation and preservation, Thomas both in his NY remarks and then in our more casual conversation at Old Town explains the foundational importance of caring: "The most brilliant landscape compositions, if neglected, will swiftly fade from visibility and therefore from memory. Without tending, the masterpiece is lost.” That last line is what line captured Tracy and me when we heard it, and it has stayed with us. Conservation and preservation both start with caring.

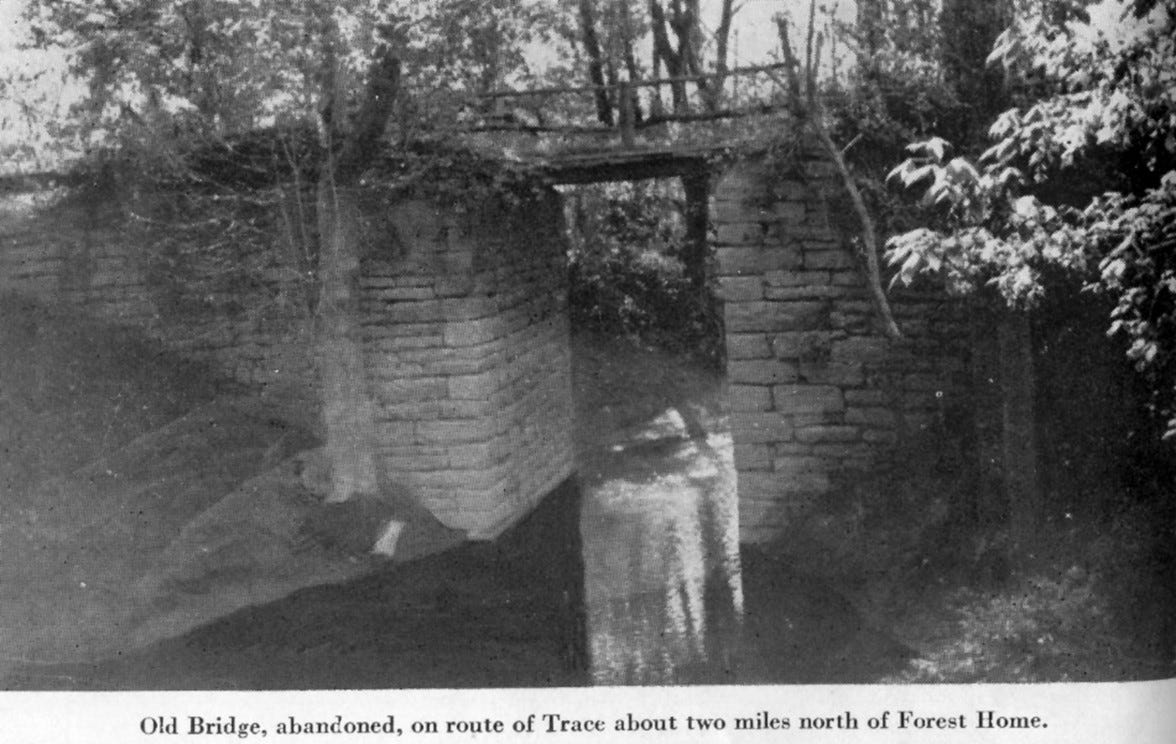

Whether we’re speaking about our early dry-stacked stone bridge from 1801, the aging grove of trees Tracy made into a formal arboretum, or the fragile cabin moved from further up the Natchez Trace and meticulously restored, the truth is the same: places matter. And unless we actively engage in preserving them, they will disappear—and with them, the layers of memory and meaning that define our shared identity. These layers shape who we are and how we act today and, importantly we believe, how we make decisions for tomorrow.

Conservation and preservation are not abstract values. Tracy currently serves on the board of the National Trust for Historic Preservation, and I serve on the global board of The Nature Conservancy. We see conservation and preservation not as separate, but as one. Both are acts of care. They require intention, investment, and yes, sometimes more than a little work.

But the reward is profound. When we preserve a place—be it a stretch of forest, a meadow, a backyard garden, a playground, a structure, or a family farm—we offer future generations a thread to the past and a deeper connection to the natural, enduring rhythms that sustain us. We root people in time and place. That brings stability. That brings security. That brings confidence and fulfillment.

Immersion to Hold the Mind in Wonder

As we walk Old Town from the smokehouse to the meadow, through historical plantings and towering trees, we’re reminded of Thomas’s remarks from the other night where he describes what he strives to capture in immersive environments, “spaces that continuously hold the mind and eye in wonder." That’s exactly what we aspire to at Old Town. It’s uncanny how often our guests tell us they feel something special when they walk the land. They relax. They feel their heart rate come down. Their breath deepens. Children race across the pastures. Adults noticeably linger longer under the trees, studying leaves rustling in the wind.

On our walk about with the visitors this last week, some gravitate toward the goats and sheep in the back, the chickens and geese (and now three ducks) in the side yard, or Bonnie, our lovable, stalking border collie, who never tires of herding whatever is wandering around. Tracy’s cutting horses move gracefully in the arena, and a colt runs the fence line—all within 50 yards of the 175-year-old clapboard home. This is not a curated show; it’s an organic, breathing, living experience.

We want people to feel this sense of immersion, of wonder, of belonging, that Thomas talks about. In a world of speed, disruption, and noise, we all need it. It both quiets us and energizes us at the same time. And that only happens when a place has been thoughtfully tended to. Immersion, Thomas reminds the crowd with us, isn’t accidental. Tracy and I are not experts at stewardship, but we are on a journey to become better. It comes from attention to detail—from restoring the early pioneering log cabin known as Locust Grove to preserving a milking barn that might otherwise have been lost. It means honoring the natural topography rather than reshaping it.

And it means for all of us resisting the temptation to develop every flat piece of land and instead recognizing that even flat land has a story. As Woltz reminded us: "Just because they’re flat, they get paved." Indeed, almost all of the other ancient Mississippian villages like Old Town are now shopping centers or building sites. Lost forever. That sentiment captures a dangerous assumption we too often make—that land exists to be altered rather than appreciated. But the truth is, conservation and preservation call us to humility. They remind us that the land does not belong to us; we belong to the land. And when we listen closely, it has much to teach. (Homo sapiens evolved around 300,000 years ago; land as we know it today approximately 500 million years ago.)

Stewardship as a Catalyst for Salvation

Old Town is not a public park, but over generations it has become a place of public meaning. We open it to friends, to students, to researchers, and to curious visitors who want to experience a different pace of life. A slower pace. A healing pace. To many, a spiritual place. Each of those visits is an opportunity for connection. Each connects in their own way. People come away not just with memories and photographs, but with a renewed sense of perspective. They feel what Woltz so eloquently calls "a constructed, living painting full of intent."

But here’s the thing about paintings—especially those made of soil and stone and living things. They don’t stay beautiful on their own. They require care. That’s where stewardship comes in. Conservation is not about preserving land in amber. It’s about actively engaging with it, learning from it, and ensuring its stories are not lost. At Old Town, that has meant us actively researching the ancient past, surfacing stories never told. We’ve worked closely with the Smithsonian Institution and Native American peoples. We’ve conducted GPR (ground-penetrating radar) to help us understand life as it once was—life that still echoes beneath our feet and where we sleep each night.

Every effort is a balancing act: productivity with preservation, working landscapes with ecological restoration, beauty with utility. From prescribed burning to riparian buffers, from turning reclaimed chestnut wood into our kitchen cabinets to restoring native grasses and historical plants, Tracy and I do our best to calibrate this balance daily. And we know we’re not alone. All across the country, individuals and families are rediscovering the profound meaning that comes with stewarding land and nature and associated structure.

Thomas Woltz reminds us: "A group of private citizens can be the catalyst for salvation seeing what had become invisible.” That has been our experience. Change doesn’t begin in the halls of Congress. I have been there; I know that. But it can start with one person protecting a field, restoring a wetland, or opening their land to others for reflection and learning. In that way, conservation becomes a moral act. A civic act. A hopeful act.

A Better Future for You and Me

In the end, preservation and conservation together make us better people. They teach us patience and humility. They encourage empathy—not just for other people, but for the natural world and all its interconnecting systems. They slow us down. They sharpen our senses. And they offer us something increasingly rare in this modern world of misinformation: perspective.

So, whether you are walking a trail, planting a tree, saving a structure, or simply spending time outside with your children, know this: you are engaging in an act of preservation. And in doing so, you are helping ensure that future generations have places of beauty, of meaning, and of healing to call their own.

Old Town, for us, is an act of gratitude. And it is a reminder that all places matter—especially those that speak softly, slowly, and with great love. As Woltz spoke in his ode to place: "From the moment of arrival to the sad moment of departure," the land holds us in wonder. May we do the same in return.

Read more about the history of Old Town at https://oldtownfranklin.com/

Mindful precious words to a fragile awareness of history thankyou Clare

Thank you for this vital journey via history & nature on the path to the remembrance of Memorial Day.